I want to write something happy

I can’t remember what it felt like to live alongside him. But sometimes I see it in flashes. Sometimes I piece together the end in flashes, too.

CW: Child death

I can’t remember what it felt like to live alongside him.

But sometimes I see it in flashes.

Sometimes I piece together the end in flashes, too.

Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death in patients under the age of 25. Nearly all transportation fatalities—motor vehicle collisions, plane crashes, pedestrian incidents—are determined as blunt force trauma upon forensic autopsy. You are statistically more likely to be struck by lightning than killed by a falling tree.

You’ve been to the Zoo, right? The St. Louis Zoo, I mean. You gotta go. It’s free.

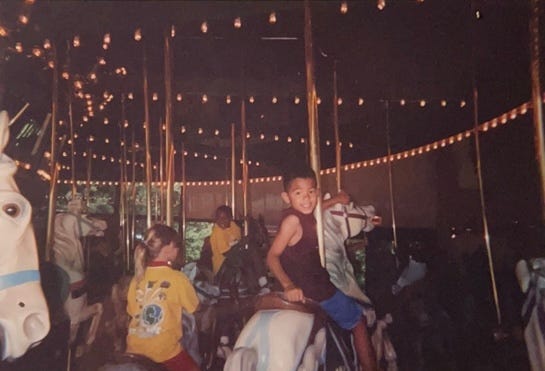

If you head east on I-64—from the Zoo toward the home my parents bought in 1996—there’s a billboard placement. In about 2004, a gorilla grinned toothily in the center of that billboard. CAN YOU COME OUT AND PLAY? requested the tagline surrounding the ape’s headshot. And Corrina, my other first cousin turned only first cousin, pointed at the gorilla every time we passed. It’s the first bit I remember.

“There’s your pitch-er, Josh. It’s your pitcher again.”

We melted into giggle fits and animated dinosaur franchises and bedtimes just after sunset.

In the early evening hours of June 10, 2013, Montgomery County, Maryland was beginning to soak up the previous night’s heavy rainfall. A few days prior, Edward Snowden evaded the Central Intelligence Agency, headquartered a 15 minute drive away (assuming no traffic) (a bold assumption). “Blurred Lines” had yet to emerge as the nauseating song of the summer. And Josh, the fifteen-year-old brother I never had, slipped out his back sliding doors and never came home.

There are moments I see so clearly, by way of my family’s militant storytelling, that a less honest version of myself might call them memories. Squished into a single Schnucks race car grocery cart, we blabbed over each other in a shared language lost to preschool summers, and shoved toward the steering wheel. “Be nice to your mother!” some old man thundered. But he only turned up the volume.

Cupping the phone in his clammy porcelain palms. On the line with his mother, Auntie Angie. Before she was my mom, Mom was Auntie Shawn to Josh and Corrina. Working in early childhood education meant Auntie Shawn had summers off, and she could take care of Josh and Corrina from June to August. This particular night, Auntie Shawn had refused Josh and Corrina dessert on account of some amorphous bad behavior. I wish I knew whether the punishment matched the crime. Josh stuttered in disbelief. “What’s she gonna take away next—breakfast?!”

We didn’t get the incomprehensible call until the afternoon of June 11. I dangled one leg off the basement couch, catching cool air on the pages of my Candy Apple book. Mom told me later that she had just mentally acknowledged an upward trend for herself, for me, for the family. Before her shriek vibrated through the vents.

“He didn’t make it,” is what Auntie Angie kept saying. Uncle Sherman found him. Josh was riding his bike off-trail in Rock Creek Park, and a tree fell on him. He didn’t suffer. But he didn’t make it.

His Beats earbuds were still lodged in his ears. He couldn’t hear anything.

Later, I meant to find out what song he was listening to. Either his phone was totaled, or I never asked.

When we last saw each other, “Stay” by Rihanna was his favorite.

It was just as Albert and I officially started dating. He wanted to show me Hereditary, Ari Aster’s 2018 debut feature. I hemmed and hawed about disliking horror as a genre (a chill girl understatement). “It’s not very horrific,” he appealed. “It’s more of a very intense drama. I think you genuinely might hate me for it, though.” I laughed. I’ve seen the uncut American Psycho and We Need to Talk About Kevin. I could handle an unsavory image or two.

What I could not handle were the images at the core of the film: a child’s severed head, and a mother writhing on her knees, howling, “I just wanna die.” Images I didn’t allow myself to conjure even when intrusive thoughts were otherwise hollowing me from the inside out like a gutted pumpkin.

Occasionally, Toni Collette’s anguished cries ricochet from the satiny surface of my pillow to my eardrum and back, and I wonder if I do hate him for it.

You start to notice fallen trees everywhere.

A wind advisory mutates into weaponry.

With every storm comes a worst-case scenario.

“Watch where you park,” Mom offers. I make a point to sidle all four tires up to the widest trunk on my side of the street. I remember statistics are on my side. A merciful God’s odds. Not Ari Aster’s.

“They say” is an oft-uttered refrain when my family members prepare to impart some sourceless wisdom.

“Who is ‘they?’” I always want to demand, but out of respect for my elders, I never do.

They say the seventh and final stage of grief is acceptance. But I disagree with them, whoever they are.

In order to experience grief, to cup your hands around the feeling, you have to acknowledge it’s there. You have to accept the insurmountability that is living alongside it, from the phone call forward.

What I’m realizing is that I’ve never really grieved. I sobbed. I screamed. I self-flagellate if I let a day pass without thinking about him. But none of it counts as grief, because all of me doesn’t believe he’s dead.

Josh is frozen at fifteen. He is youthful and accomplished in a place I can’t visit, and not because it’s six feet underground, or on a cloud in the sky. This is the version of loss I can live with. My brain—no, my entire body—won’t tolerate any other.

I want to accept that I no longer live alongside him. But I don’t think I ever will.

We are laughing the lining off our stomachs.

A giggle fit in the backseat of our grandmother’s Nissan Altima. Except it’s just Corrina and me. Josh isn’t even smiling. He’s plugging his ears and pleading for it to stop.

My grandma, who we call Momma D, is in on the joke. Every three minutes, she flicks a button near the CD player and restarts “Linus and Lucy,” the main theme from A Charlie Brown Christmas. She spins laps up and down the hill that leads to her house. The piano loops for at least an hour. We are high on the pleasure that is teasing our brother and cousin and grandson, respectively.

Momma D recalls that memory often.

I collect Peanuts memorabilia now.

One Sunday night, I drove home, cloaked in cloud cover that threatened to burst into hysterics before I made it inside the garage. I barely remembered why I left in the first place. Because my house was too heavy, I guess. My mother had just returned from Cleveland, where my great-uncle Melvin lived a long, relatively healthy life, and died. She brought the cemetery to the couch, where she sat before the cracked leather ottoman in the center of the living room as though it were the casket. So down the driveway I went, in search of reminders that this was indeed the land of the living. I parked just off South Grand Boulevard and creaked up the back staircase into my best friend Lilia’s apartment. Reruns of The Real Housewives of Atlanta filled the space where I might have otherwise admitted that I came over to escape the rituals of mourning, like I always have.

Back in the garage, safe and dry, I hoisted my bookbag over my shoulder from the backseat. My empty glass kombucha bottle (which my mom liked to reuse) slipped out of the mesh side pocket and shattered on the ground. Dazed and disaffected, I palmed the biggest shards into the trash, forgetting their power to draw blood.

My mom appeared in the doorway, clearly roused by the racket.

“The bottle fell and broke.” I trudged inside, chastising myself for drawing so much attention to my late arrival.

“It’s okay,” she said serenely, the way only a light sleeper can. “Accidents happen.”

People say that more often than they are willing to accept it.

I’ve told you a lot about who Josh was.

Now I want to tell you who he might have been.

I want you to know that Josh aspired to go to flight school and become a pilot. Brigadier General Charles Edward McGee, one of the last living Tuskegee Airmen at the time, delivered the eulogy at his funeral.

I want you to know that in the margins of his resume, at the would-be outset of his college application process, next to his unweighted GPA, Josh scribbled, “I need to put away childish things and get my grades up.” The King James Version of the first book of Corinthians, chapter 13, verse 11, reads, “When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

I want you to understand that everything was lining up for him.

I don’t understand why it had to stop.

About a month after our Hereditary attempt, Albert puts on Porco Rosso, a Miyazaki classic. There’s this scene where the titular pig pilot tells Fio, his underestimated girl mechanic, a wartime story. He recalls blacking out during battle and coming to within a brilliant cloud. His suddenly self-flying plane ascends, hovering atop the cloud, and from here a swathe of swirling light particles can be seen in the distance. Porco Rosso marvels as all around him, downed planes and their deceased aviators—comrades and enemies alike—float toward the far-off shimmer. He begs a dear friend to stop, vows that he’ll go instead. But it’s no use. They all depart for luminescent, infinite flight.

Occasionally, the interplanetary Studio Ghibli score reverberates from the satiny surface of my pillow to my eardrum and back, and I know I will always love him for it.

I try to imagine him in an abstract place like that. An afterlife suited for the whimsies and innocence of a child, which he still was.

Because I’ve never grieved, though, he doesn’t belong there.

As the years without him begin to surpass the years we had together, even I have to admit he doesn’t really belong here, either.

I cannot place Josh in a lecture hall, or behind a KN95 mask, or in a cockpit, or next to his girlfriend on the couch.

But I know it was something to live alongside him. In the backseat, and in the grocery store, and in the lyrics of a Black beauty mogul who doesn’t make music anymore (sorry, Navy, I had to), and in the plot of every movie.

I wanted to write something happy

And now that I’ve written this, maybe I can.

Kennedy, your writing is just gorgeous. Emotionally, lyrically, vividly gorgeous. This is a real feat. I can't wait to read that something happy, or anything else you write. <3

so incredible.