Lofi Gaze

(un)Changing Representations of Women and Girls in Global Visual Culture

She hunches over a fashionably cluttered desk, resting her chin in her right hand. Her left hand clutches a black ballpoint pen. She positions it above a blank page in her unlined journal and begins scrawling illegible notes in meticulous, evenly spaced penmanship. With a single paragraph written, she perks up and glances over at the orange tabby cat to her right, perched on the windowsill, swinging its tail like a pendulum. Less than halfway down the page, she settles back into her dutiful slouch and flips to a fresh sheet of paper. The image resets and loops to an Internet-specific infinity. Downtempo hip hop scores the scene, the source of which is her over-ear headphones (or so it’s implied). Outside her window—depending on the time of day one sees her—a pastel cityscape either bakes under sunlight or soaks up a downpour after nightfall. Save a fleeting look in her pet’s direction, the world beyond her room passes her by without so much as an observation. The sole objects of her slightly bored but diligent gaze are her study materials. She isn’t the girl next door because her neighbors probably aren’t aware she exists. But at any given moment, tens of thousands of people watch her work. Over ten million people subscribe to her YouTube channel. Also, she is not real. Her name is Jade. Most call her Lofi Girl. Lofi Girl exposes a global obsession with visual representations of girlhood that echoes a lineage of objectified women in portraiture.

To understand Lofi Girl and the phenomena that surround her, one must first identify the original image upon which her appearance is based. The image in question is a brief scene from the 1995 Studio Ghibli animated film Whisper of the Heart, directed by Yoshifumi Kondō. Shizuku, the film’s protagonist, spends her afternoons reading and writing fairy tales, including the titular story. Dimitri (last name unknown), a Parisian in his mid-twenties, initially selected a GIF of Shizuku in her bedroom as the visual that would accompany his “lo-fi beats” livestream, ChilledCow, which launched in February 2017. Unexpectedly, the channel soared in popularity, with thousands of viewers worldwide tuning in at all hours of the day to “relax/study” alongside Shizuku. ChilledCow’s meteoric rise landed the livestream in hot, copyright-infringed waters, and in August of that year, YouTube took it down1. Colombian animator Juan Pablo Machado promptly answered Dimitri’s call for a new likeness, creating the Lofi Girl of today, who sits alone in Lyon, France. But Machado’s style draws heavily upon the established Studio Ghibli aesthetic: that of the works primarily directed by the animation studio’s cofounder, Hayao Miyazaki.

Hayao Miyazaki’s visual representations of Japanese women and girls fundamentally inform Lofi Girl’s sizable audience. In a 1994 article for Film Comment, David Chute points out that “[a]lmost always, the point-of-view characters in Miyazaki’s films are young girls, extraordinarily gifted but plausibly awkward kids, testing their powers in tentative interactions with the world” (65), a coterie Shizuku joined upon Whisper of the Heart’s release the following year. (Though the late Kondō directed this film, Miyazaki wrote its screenplay.) Karissa Sabine probes these narratives more directly in her 2017 thesis “Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki.” Using feminist textual analysis, she situates the protagonists of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997), and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) as “offering a counternarrative to other representations of girlhood, and ultimately, of gender by their refusal to be limited or defined” (Sabine 61). While such an argument powerfully testifies on behalf of Miyzaki’s artistic intentions and their impact on both representational politics and the gender binary itself, it does little to address the equally significant processes of objectification and fetishization at work within male and/or Western consumption of anime, which persist so long as Sabine’s understanding remains a nondominant one.

Lofi Girl cannot be divorced from anime: a medium that is at once a site of distinct cultural production and of voyeuristic consumption. Kumiko Saito speaks to this tension in “Magic, ‘Shōjo’, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society,” a 2014 essay for The Journal of Asian Studies. Saito defines the “magical girl” genre, in which “a nine- to fourteen-year-old ordinary girl accidentally acquires supernatural power…the plot often revolves around the way she wields her power to save people from a threat while maintaining her secret identity” (145), predominantly developed by Tõei Studio in the 1960s and 70s. The article questions the efficacy of various media in “undermin[ing] fixed traditional gender roles,” as well as just how “empowered” the magical girls really are (145). Selected examples, including Sally the Witch (1966-68) and Sailor Moon (1992-97) end up reinforcing “fashion, romance, and consumption” as adolescent priorities to be promptly abandoned upon marriage and absorption of the former magical girl, now ordinary woman, back into the domestic sphere (Saito 146-48). Saito then introduces the term otaku, which emerged in the 1980s to describe “fans [who] actively seek comprehensive knowledge and often have erotic fantasies about visual and textual products, thereby differentiating themselves from ‘normal’ consumers” (146), and poses major implications for a “male-oriented fan culture” and its engagement with animated representations of women and girls (143). Most telling are the target demographics of contemporary Tõei Studio magical girl programming: “both girls between four and nine years old and men between nineteen and thirty years old” (Saito 147). Magical girl anime imposes patriarchal standards on its impressionable female viewers, while fulfilling the perverted imagination of its otaku sector. Though it is most often associated with television series, the magical girl genre and subsequent character trope appears again and again throughout Miyazaki’s filmography, and is therefore influential on anime as a whole. At once “convey[ing] messages about gender roles reflecting standardized social norms” and generating “a vortex of representations operated by visual fetishism of young female bodies” (147), magical girl anime continues to replicate harmful patterns of viewership of women by Japanese audiences—and, more broadly, by Japanese society. This is to say nothing of the fetishization inherent within Western relations to Japanese media.

The anime girl as a fetish object transcends borders and cultures, and a legacy of exoticization and Orientalism enacted by Western viewers compounds its harm. In the introduction to her 2013 thesis “Silence of the Schoolgirls: Death and the Japanese Schoolgirl in Contemporary U.S. Pop Culture,” Dana DeLauss establishes “how commodity culture mediates the cultural relations between the U.S. and Japan,” relations which are “largely based on…encounter[s] with images of gendered identities in Japanese pop culture” (3). Her examples of such encounters include the 2001 film Suicide Club and Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke (1, 16-17). DeLauss rejects the argument that the otaku subculture and its male participants “demonstrate a ‘wishful identification’ with the plight of young women and desire to introject into young, female subjectivity” (3-4). Instead, she is of the belief that most “images of women in Japanese pop culture” and the ways in which they are consumed across the world, but specifically within a Western context, “in fact deprive them of voice and agency” (4). This claim is particularly useful when evaluating the persona assigned to Lofi Girl, a silent figure who is unaware of her thousands-strong audience and never afforded a chance to confront them directly. In broadcasting one image inspired by countless representations of Japanese women and girls in anime, that image and all of its influences are denied ownership of their gaze.

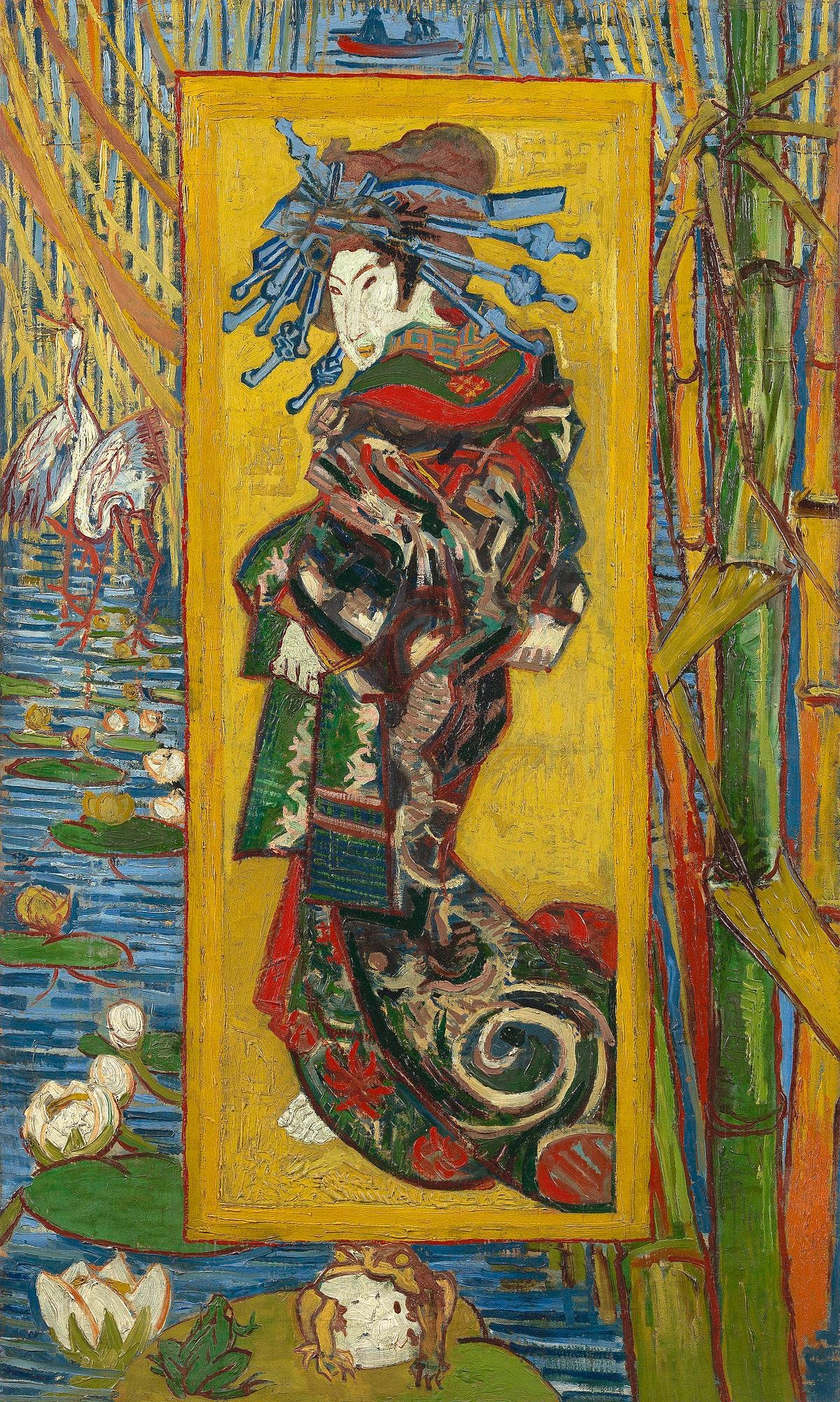

Issues of objectification and ownership have plagued images depicting women and girls since long before the earliest anime films of the 1900s and 1910s (Litten 27). Dana DeLauss also references Japonisme, the Western arts movement that slightly preceded the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which brought Japan’s two-century “feudal period of isolation” to an end (25). Esteemed Dutch and French artists Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet contributed oil paintings of Japanese geishas and white women dressed in kimonos, respectively, in addition to amassing their own personal collections of Japanese woodblock prints called ukiyo-e paintings (26-27). Such creative practices reduced the Japanese woman to “an accessory or collectible image” (27), and further entrenched objectification patterns along gendered lines and patriarchal power dynamics (it’s worth mentioning that Monet’s model for his 1876 work La Japonaise was none other than his wife). On the whole, Western art history set the stage for a tradition of non-autonomous representations of womanhood and girlhood that persist into the present.

Aside from Whisper of the Heart’s Shizuku, the host of magical anime girls like her, and the painted ladies of the Japonisme, Lofi Girl finds perhaps her most striking parallel in an unlikely locale: a portrait of Phillis Wheatley, America’s first published Black poet. Wheatley sits for this portrait in side profile. One hand rests delicately on her face in “a typical gesture of melancholy,” according to Astrid Franke, “whose associations with sensibility and inspiration rendered it a desirable attribute of poets and thinkers” (226). The other clasps a quill; the unknown engraver captures Wheatley in the middle of jotting down a thought. Her gaze is not trained downward at the sheet of paper in front of her, though—she looks decidedly past the frame around which her name appears. If, as Franke asserts, “iconographic elements survive across centuries, reoccurring and recombining to form new ideas within a living tradition” (227), perhaps Wheatley’s gestures stand to be interpreted not as hallmarks of “a mournful reflexivity” (227), but rather as the makings of a countervisual, in which the racialized woman depicted exercises full control over what she sees. With this understanding in mind, the beloved Lofi Girl represents the magical anime girl, the prey of otaku, an accessory to digital life, a gazeless image of female adolescence, and the melancholy muse...if and only if she neglects to look up.

Works Cited

Chute, David. “ORGANIC MACHINE: The World of Hayao Miyazaki.” Film Comment, vol. 34, no. 6, 1998, pp. 62–65, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43454630.

Franke, Astrid. “Phillis Wheatley, Melancholy Muse.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 77, no. 2, 2004, pp. 224–51, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1559745.

DeLassus, Dana. “Silence of the Schoolgirls: Death and the Japanese Schoolgirl in Contemporary U.S. Pop Culture.” The University of Texas at Austin, 2013, pp. 1-65, http://hdl.handle.net/2152/21422.

Litten, Frederick S. “On the Earliest (Foreign) Animation Films Shown in Japanese Cinemas.” The Japanese Journal of Animation Studies, vol. 15, no.1A, 2013, pp. 27-32.

Sabine, Karissa. “Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki.” Oregon State University, 2017, pp. 1-60, https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/b5644x18k.

Saito, Kumiko. “Magic, ‘Shōjo’, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 73, no. 1, 2014, pp. 143–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43553398.